How to enter a space

ein Beitrag des Medienkünstlers Michail Rybakov

Michail Rybakov is media artist, researcher and member of the »Critical Zones study group« at Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design. The main topic of his work is embodied interaction and human experience in the post digital world.

I have talked about how maps misrepresent space in a previous essay. But what if it is not just the representation that is flawed, but our presence in space makes it not as rigid, not as Euclidean as we may expect? Think about the moment you enter your home after a long journey. At first the space seems strange, the rooms are weirdly sized, seem familiar and yet different. A bit out of place. It takes a few moments for the feeling to disappears, for you to arrive.

Even though we often forgot about it during the research seminar with Bruno Latour, the end goal of the seminar was always a real-life exhibition in an actual museum space. And we would need to find a way to deal with this space, and with the arrival in it. You can try and view the museum space as a Foucauldian ‘heterotopia’. Or as an Oldenburgian ‘third place’. Or as a place that offers ‘affordances’ to its visitors. Or even as an institutional space if you are so inclined.

I was much more interested in seeing the space as an active element. What does the room do to my body? Where does the room place me, as I enter? How does the space allow me to arrive? And can it be consciously designed?

Here are a few »situations« that I created to experiment with these questions.

A soft entry

There exists one thing that we are touching almost constantly, all the time. It is the ground beneath our feet. Walking, standing on the ground can be seen as an act of rejection - we reject gravity, we push the ground away from us, we decline the proposition of giving in, of falling, of belonging to the ground. In such an antagonistic relationship to the ground it is not easy to see the act of walking as an act of touch. And yet, we touch the ground with every step. We feel texture, inclination, slipperiness and hardness of the materials we step on.

»Soft entry« was a proposed design for the entrance to the upcoming Critical Zones exhibition. A soft mat would cover the area, soft enough to force a re-adjustment of posture and changing the muscle tone of the arriving guests, but not too soft as to not divert the visitor’s attention to itself. This barely-perceived physical effect should change the feeling of the space in people entering the exhibition. It should change how they, bodily, relate to their surroundings.

I did a test with it for four days during the Critical Zones seminar in January 2019. It seemed to work well enough the first few times, though many tried to enter the room without stepping on the foam mat. I attribute this effect to the mat not looking like something that you would traditionally step on.

In my unscientific survey, the mat did create a feeling of entering a different space. Whether it was caused by the looks of the unconventional threshold or by the feeling of the soft ground is debatable. Covering the foam with more common ground mats could further reduce the friction of stepping on the soft entrance area.

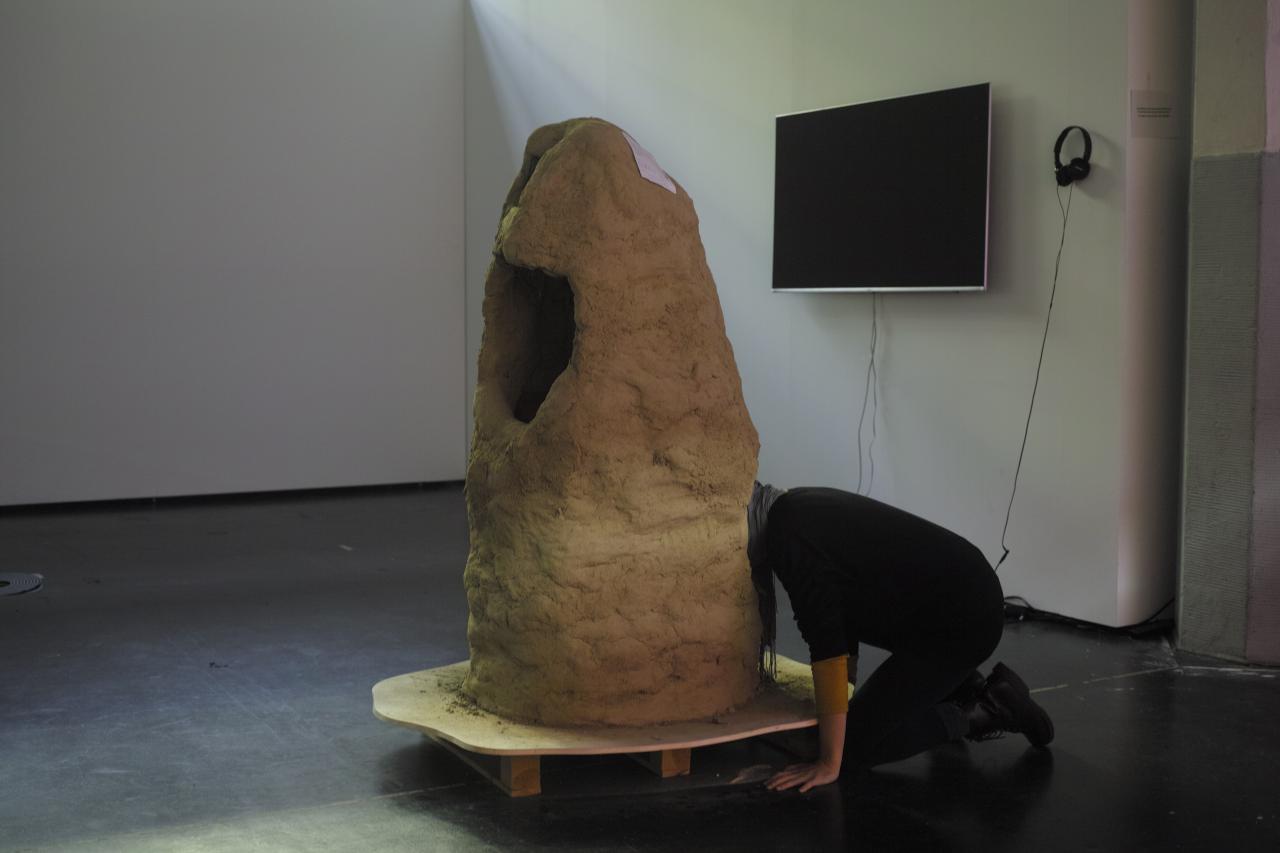

The hiding place

This sculpture is made of loam (and built by Lukas Marstaller and Oliver Boulam) looks a bit similar to a termite hill. It has two openings, just large enough to put your head inside. A grown person has to bow to put their head into the upper hole. For the lower one, they have to kneel.

Inside, it smells wet and earthy of loam and geosmin - a compound produced by the streptomyces bacteria that can be found in soil. Geosmin is in large part responsible for the smell of wet earth after a short summer rain.

In the other opening, it smells of sandalwood. The chemical compound called Sandalore is responsible for the smell and was shown by researchers of the University of Manchester to stimulate hair growth by regulating the lifecycle of hair follicles (in vitro, but still!).

In both head rooms a sound can be heard. I fed hours of recordings of Sir David Attenborough and Werner Herzog to some neural networks called SampleRNN, which learned their voices and pronunciation. It did not, however, learn the content of their speech, and the sound generated by the machine is pure gibberish. While it may sound very similar to the two old wise men whom we learned to trust, telling stories about ourselves and the world we live in, it is devoid of all meaning.

Werner Herzog

Sir David Attenborough

As the visitors entered the caves with their heads, their sight was blocked by the darkness, the sense of smell filled by the smell of wet earth, their hearing calmed by the soothing, nonsensical narrations of the storytellers. With the most important senses hidden away in the head cave, only their derriere was exposed to the outside world. It might seem unfair to call the entirety of the human body – with the exception of the head – derriere. But for many of our daily activities, it is exactly what it is – a device to sit on.

»The hiding place« is a kind of a non-place. Like a child that believes that by closing its eyes it becomes invisible, you too for a moment exit the museum space and enter a nothingness. You don’t have to give attention to your facial expression as now, finally, you are not being seen. Your body may be exposed, but so what, you are turning your back on the world. You are bowing or kneeling, which would be a sign of submission, but you are outside of the social now. You are listening to calm authoritative voices, but they tell you nothing in particular, just that they exist and you may rely on them. You smell the earth and are transported even farther outside of the noisy, overwhelming museum, away, to the lands where earth is wet under the pines, the summer rain has moved on and you still have some time until dinner is ready and your grandma calls you home.

The reading bike

The reading bike is constructed upon a cargo bike made by SARNES engineering. Some wood scraps are added, some screws, a wheel from a broken bicycle, general leftovers from the process of living, objects that were once part of something bigger but lost their function and history. Out of these discarded materials, a contraption is built which rotates a tube in front of the driver when the bike is being driven. The tube’s rotation advances the roll paper and through that, the text. The reader must exert force, must change their position in space in order to change their position within the text.

I have presented the bike with two different texts. One was a poem by Hermann von Hermannsthal, a poet of romanticism. It is called »Wenn ich den Wandrer frage« (When I ask the wanderer), which could be translated like this:

When I ask the wanderer:

«Where do you go?»

«I go home, go home»

he says with a cheery tone.

When I ask the wanderer:

«Where lies your fortune?»

«At home, at home»,

he says with teary eye.

When he finally asks me:

«What distresses you so?»

«I cannot go home,

have no homeland anymore».

Which worked quite nicely as a reference to the imminent and seemingly inexorable loss of our planetary home to climate change – which was also the context of the exhibition. The reading bike makes you the wanderer, going on further through space in order to read the writing on the wall roll. The wobbly, insecure contraption on which you sit just adds the sense of precarity, the familiar sense that many feel nowadays when trying to imagine their future.

Laura Haak riding the »reading bike«

The other text that I used was a collection of haiku-like poems, written by me and intended to confront the reader with their bodily position on the bike, with the physical space they are in, as well as within the current moment in the vast history of earth. Here are a few:

above you

up in the sky

a swallow flies

two years ago

a couple kissed

standing right here

when you inhale

the air you breath in

your neighbour exhaled

right through you

the Wi-Fi signal goes

checking your mail

when you were young

right in this place

two bees collided

a few lifetimes ago

a forest stood here

a forest will grow here soon

if you wait long enough

once in a while

a happy person walks by

The first version of the bike rotated the paper upwards, against the reading direction. That is why the poems are written in a way that allows them to be read from top to bottom and from the bottom to top.

The bike was built to experience the sensation of having to move through space in order to move through text. It does so in a very exposing way, since, contrary to the situation with »The hiding place« your head and face remain visible, maintaining your social presence. The unstable position on the bike and the need constantly move makes your social body as well as the physical body feel vulnerable, and the three spaces – the social, the physical, and the textual become increasingly harder to navigate.

Some riders were able to read the text easily, disregarding their social and physical standing, while others were constantly switching their attention. It appears to be a very polarizing exercise.

After doing these experiments it seems apparent that entering a space is not limited to the physical act of being present in it. There is a moment where space (as designable structure) transitions to place (emergent from social practice). I am in a space but I relate to a place. The relationship to place does not hinge on people being present in it. I relate to my role in it, to what I am in that place.

In the moment of arrival something happens that we normally choose to ignore: for a split second the social roles get readjusted and the body recalibrates to new surroundings. And while it may feel near instantaneous, there could be a way to influence this process. What needs to be designed is not the space itself, but the interruptions, the interventions, the excuses that shake up the social and physical bodies that inhabit the place. Whether by adding a disorienting but understated element like the soft entry, or an opportunity to visibly escape like the hiding place, or a way to disentangle movement in space from its social meaning, like the reading bike.

Place is how you relate to your surroundings. And the process of relating can be designed.

Ein Beitrag von Michail Rybakov.

See more of Michail Rybakovs' works and essays on his website.