Aby Warburg – Biography

Ebreo di sangue, Amburghese di cuore, d’anima Fiorentino

»Jew by birth, Hamburg at heart, Florentine in spirit.« Aby Warburg was born in Hamburg in 1866, some twenty years ahead of the generation from which the driving forces of modernity would emerge. The eldest son of a Jewish family that ran a prominent banking firm, he was unwilling to reconcile himself either to a future in business or to the religious strictures of his family, so he proposed a trade to his younger brother Max: in return for the firstborn son’s right to take over the bank, Aby asked that, for the rest of his life, any books needed for his studies be paid for. From this arrangement, the Warburg Library would be born.

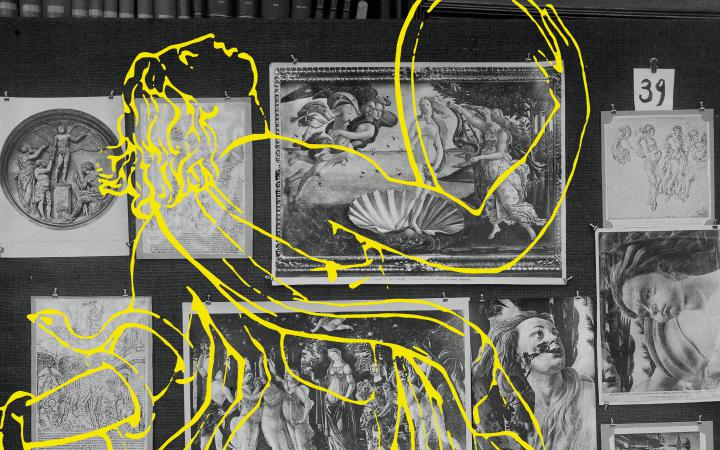

Warburg studied art history, submitting his dissertation on Sandro Botticelli’s Venus and Primavera – the first example of a modern approach to the discipline – in 1892. The “border police bias” of his colleagues at first drove him from his field of research, and he considered starting on a second degree.

But a visit to the Hopi during a trip to the United States in 1895 dispelled his doubts. The compact, almost striking clarity of that indigenous culture, its direct connection of myth, image, and ritual, brought him back to the central theme of his research: the survival of antiquity in the Renaissance, as manifested primarily in a time of great conflict, the mid-fifteenth century – that is, long before the praised masterpieces of the High Renaissance were created.

In 1897, Warburg married the artist Mary Hertz; they spent the first years of their marriage in Florence. He explored the city’s archives, where he came into contact with prominent scholars such as Giovanni Poggi, Herbert Horn, Jacques Mesnil, and André Jolles. Warburg and Jolles collaborated on a study of the nymph, that refreshingly lively figure that lightly trod the ground of the Early Renaissance – a strangely exotic apparition in an environment of Christian modesty. In 1902, Warburg returned to the city of his birth with his wife and their two children, born in 1899 and 1902. A third child was born in 1904.

Warburg became very active in Hamburg’s cultural life and expanded his collection of books. In a lecture on Dürer and antiquity, he coined the term “Pathosformel” [pathos formula]; soon he was speaking of “Bilderfahrzeuge” [image vehicles] as well, those portable carriers, such as carpets, prints, and oil paintings, that made images mobile and dominated international communication along the “Wanderstrassen der Kultur” [pathways of culture], another of his coinages. He discovered the writings of Franz Boll, which opened up the field of astrology to him and drew his attention to the long distances by which the knowledge of antiquity had passed through the Arab world before returning to the European cultural sphere. Building on this foundation, Warburg was able, in 1912, to solve the riddle of the frescoes at the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara, Italy. No one before him had realized that they must have been painted according to a detailed plan including descriptions of all the characters: the gods and heroes of Greek mythology, retranslated from Arabic sources.

By this time the library in his house in Hamburg was already an institution, open to other researchers and overseen by Fritz Saxl. As World War I approached, Warburg noted with increasing concern the enormous extent to which the people were seized by superstition in time of crisis, a problem he illustrated in a text on Martin Luther and his relationship to astrology.

Warburg had been plagued since his youth by depression; now the war increased the danger of loosing his balance. He turned his house into an observatory for war propaganda, made plans to exhibit the material in a “Museum of Lies,” and, as the war came to an end with Germany’s capitulation, suffered a nervous breakdown. This crisis kept him confined to various psychiatric institutions for six years. In 1921 he began therapy at Ludwig Binswanger’s Bellevue clinic in Kreuzlingen on Lake Constance. There he gradually regained his stability, taking a major step on his own in 1923 when he gave a lecture at the sanitarium on the Hopi snake dance. In making this now-legendary attempt to return himself to the role of the scholar, Warburg was, on one hand, describing and visualizing a quite unusual, even frightening ceremony and seeking to determine its function in the context of its culture; on the other, he was performing self-analysis and recollecting his own expedition to the Hopi.

His recovery was also aided by visits from Saxl, who built the Warburg Library into a major institution during these years. Warburg himself saw his correspondence with the philosopher Ernst Cassirer as providing vital encouragement. Cassirer, who had been the chair of philosophy at the Universität Hamburg since 1919, acknowledged Warburg’s research and provided valuable advice, particularly with regard to his assessment of the importance of Johannes Kepler.

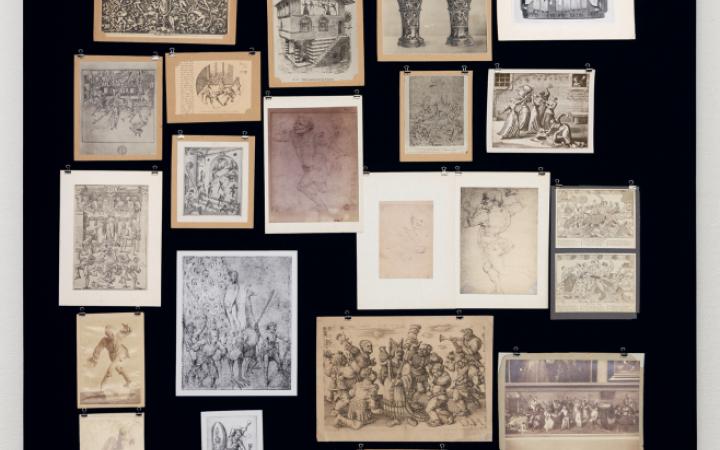

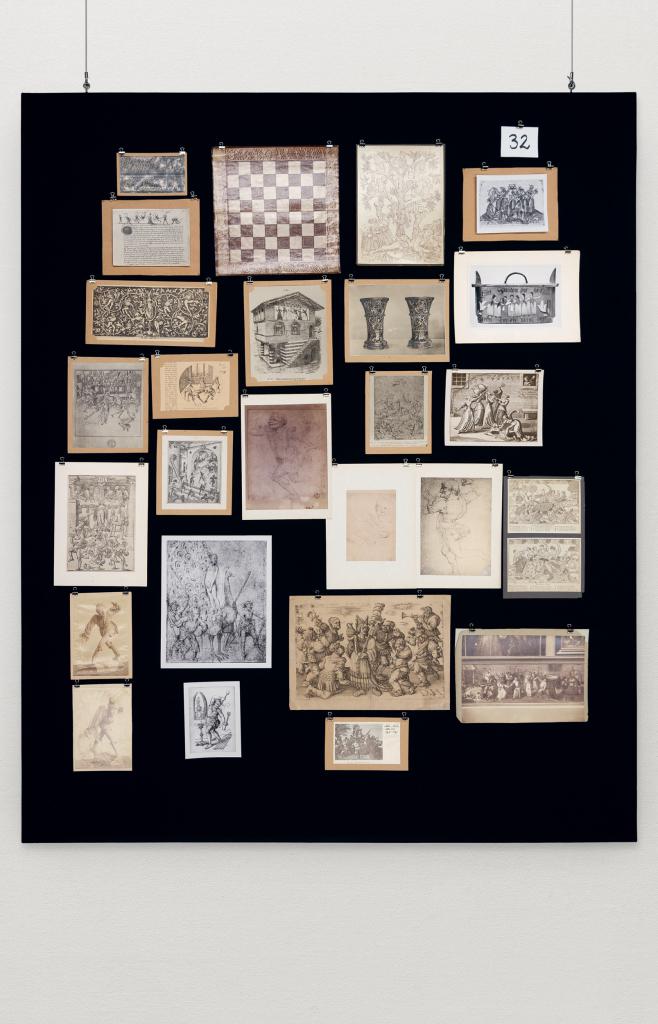

Warburg was able to return to Hamburg in 1924. He took over as director of the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg (K.B.W.) [Warburg Library of Cultural Studies], which by then had become a leading research institution, and embarked on a demanding schedule of lectures accompanied by “Bilderreihen” [image sequences]. This “technique” formed the basis for his last major project, the Mnemosyne Atlas.

In 1926 a state-of-the-art new facility housing the library was opened next door to Warburg’s townhouse. In the years that followed, the library became home to a research community that would go down in history as the “Hamburg School”: Erwin Panofsky, Edgar Wind, Gustav Pauli, Raymond Klibansky, Ernst Cassirer, Fritz Saxl, and Gertrud Bing – to name just the most famous and the inner circle. Warburg constructed the Mnemosyne Atlas in the midst of their discussions, where he tested it out, expanded it, and refined it, intending to present it to the public in the form of a substantial book.

In the spring of 1928, the first version of the Mnemosyne Atlas, consisting of forty-three panels, was documented in photographs; a second version, with more than seventy panels, followed in the fall. Warburg traveled to Rome to conduct the “final rehearsal” of the project at the Bibliotheca Hertziana. A third version of the atlas was begun in the summer of 1929 but had not yet been given final form when, on October 26, Warburg succumbed to a heart attack.

________________________________

Text: Axel Heil, Margrit Brehm and Roberto Ohrt