In 1997, the ZKM opened the first exhibition of computer games. Under the title »World of Games«, the exhibition, conceived by Friedemann Schindler and Frank den Oudsten, was shown in the context of the then ZKM | Media Museum. The visitors were to have the opportunity to get to know computer games as well as to gain generalizable experience with the interactivity of digital media.

As early as 1997, computer games were considered a medium that would not replace traditional mass media, but would continuously change them through its aesthetic structures and forms of distribution. Two perspectives shaped the concept of the exhibition: an art-theoretical one as well as a sociological one. Games were considered »agents of socialization« (Friedemann Schindler), since their values and explanatory patterns were seen as particularly formative for future generations.

Doom

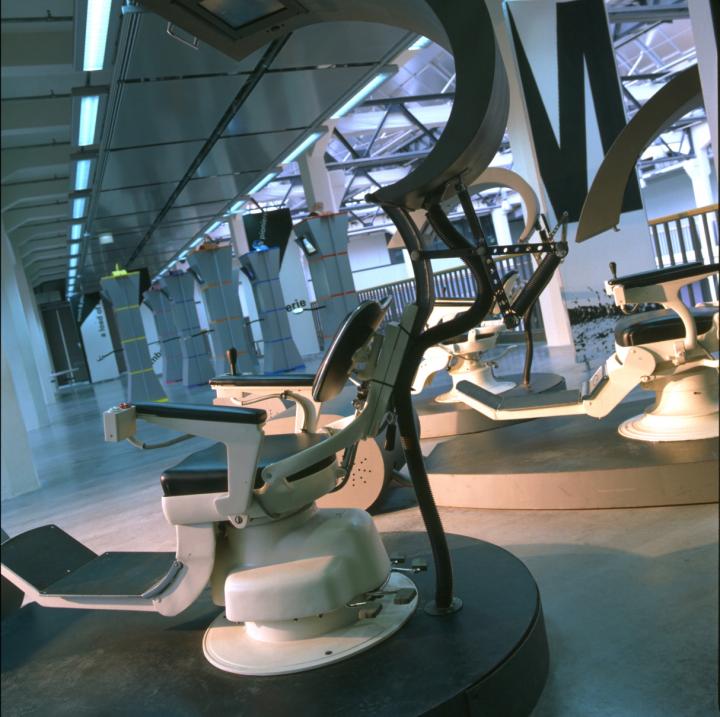

One installation was therefore dedicated to the first-person shooter »DOOM« (1993). The game exemplified the question of possible behavioral change through depictions of violence in computer games. The interface allowed the visitors to observe the players. Via two monitors attached to the foot of the chairs, they could follow which actions took place in the virtual space and observe »which traces they left on the physical-real face of the actor«. The installation consisted of three dentist's chairs. The unpleasant association was reinforced by the fact that a scene from the film »The Marathon Man« was played at irregular intervals, in which Dustin Hoffman is tortured with dental instruments – “a film sequence that shows violence only in hints and yet seems incomparably more violent than the bloody carnage in the DOOM game, which the viewer can also follow.” (»Media - Art – History«, ZKM, 1997)

Labyrinthos

The installation »Labyrinthos«, a ZKM production, was based on a historical computer game called »Midi-Maze«, the first ever net game for home computers. The players had to track each other down in a labyrinth that imitated the architecture of the real media museum. Up to eight players sat together at a gigantic console.

Licence to Kill, Lone Wolves – Helpless Princess, Good + Evil

The installations »Licence to Kill«, »Lone Wolves - Helpless Princess« and »Good + Evil« were intended to show that computer games not only act as »socialization agents« on behavioral structures, but have long had a more lasting influence on knowledge of social contexts than school teaching.

Ancestors' Gallery & Search & PlayThe ensemble of the world of games was complemented by two installations that were intended to establish a historical and analytical context: the »Ancestors' Gallery« and »Search & Play«. The »Ancestors' Gallery« showed the great importance of computer games in the way industrial societies had evolved into information societies since the 1970s. The visitors experienced »Pong«, the first video game on the mass entertainment market, as well as »Pac Man« or »Minestorm«, the game that had a blood pressure meter as a monitor, the »Wintergames« of the C64, »Lemmings«, the most successful game for the Commodore Amiga, »Tetris«, which helped the »Game-Boy« to its breakthrough, and finally »Super Mario«, perhaps the most successful art figure of all times.

The analytical background for the »World of Games« was meant to be guaranteed by the interactive database »Search & Play«: The database was intended to assist in the search for suitable games, but also to provide criteria for evaluating games. What was special and new about this was that children and young people were also included in the evaluation of games. »Search & Play« was a joint project of the Federal Center for Political Education and the ZKM, initiated in 1994.

The director of the Media Museum at the time, Hans-Peter Schwartz, conceded that since Marcel Duchamp the demarcation between art and play was no longer clear, but stressed that the »World of Games« and the works of the Media Museum were “also about keeping the differences between commercial, scientific and artistic games free. But these can only be summarized unsatisfactorily in theory, so this discourse must remain open, can be continued quite practically, not least in the media museum." (»Media - Art – History«, ZKM, 1997)

- Credits

- Friedemann Schindler (Concept)

- Frank den Oudsten (Concept)

- Hans-Peter Schwarz (Concept)