Pioneer of New Music. The composer Hermann Heiß

First published in: »Mediagramm« No. 12, July 1993

In July 1993, the then Head of the ZKM | Audio Collection, Thomas Gerwin, described the digitization project for the acoustic and written estate of the composer Hermann Heiß:

In the media library of the ZKM, the entire estate of the composer Hermann Heiß is being transferred to digital data carriers. These are audio tapes, writings, manuscripts, programs and scores, almost all of which are available at the Hessische Landes- und Hochschulbibliothek Darmstadt, from where they will be made available for digitization. The originals will be transferred to their original locations or will return there after archiving at the ZKM. In digital form, the entire collection will become part of the International Digital Electroacoustic Music Archive (IDEAMA) and will be available for public use in the ZKM Audiothek from 1996. In the ZKM Mediathek, the entire estate of the composer Hermann Heiß is transferred to digital data carriers. These are audio tapes, writings, manuscripts, programs and scores, almost all of which are available at the Hessische Landes- und Hochschulbibliothek Darmstadt, from where they will be made available for digitization. The originals will be transferred to their original locations or will return there after archiving at the ZKM. In digital form, the entire collection will become part of the International Digital Electroacoustic Music Archive (IDEAMA) and will be available for public use in the ZKM Audiothek from 1996.

When the composer and theorist Hermann Heiß died in his hometown of Darmstadt on December 6, 1966, he left behind a multifaceted and unusual oeuvre. His cross-media works, which included language, light and dance, his twelve-tone compositions, his improvisation studies as well as his sound movement theory, his pioneering work in the field of electroacoustic music and, above all, his teaching and lecturing activities, for example at the famous Darmstadt Summer Courses, provided impulses for musicians and composers from all over the world.

He was born in Darmstadt on December 29, 1897, the youngest of eleven children, and became interested in music at an early age. He writes in a letter:

"There was no place music where I didn't steal away to the conductor to assist him with a log of wood in my hand (...) With parents four-handed at the piano, we performed not only Haydn's, but also children's symphonies we had found ourselves."

After briefly trying to "learn a decent profession", he was drafted into the military in 1916. After returning from captivity in 1919, he began intensive, mainly self-taught musical studies. In 1923, when he first came to grips with twelve-tone theory, which he had "already unconsciously come quite close to" through his own work, he was faced with the choice of joining one of the two protagonists of twelve-tone music - Arnold Schoenberg or Josef Matthias Hauer. Schoenberg convinced him by his compositional work (at that time just op. 23), Hauer by his, in Heiß's opinion, more expandable basic idea of the twelve-tone technique. So he went to Hauer in Vienna for a quarter of a year in 1925 and worked with him "day and night, so to speak". This resulted in Hauer's writing »Die Zwölftontechnik«, which he dedicated to Hermann Heiß. Heiß describes Hauer as a "constantly enthusiastic person who, in obvious contrast to his character, created this form-strict manner of composition", as one who "suddenly began to quote Hölderlin or even sing in his twelve-tone movements at night on the streets of Vienna in a loud and beautiful voice." The encounter with Hauer left a lasting impression on Heiß.

Heiß wrote the »Composition E-F sharp-D« for piano during and shortly after his stay in Vienna, which became so fundamental for him that he analyzed it again in detail 23 years after it was written:

"A series of twelve tones serves unchanged as material for all movements. Such a series cannot be freely invented, like a theme, for example; it is chosen from among the many possibilities, just as a mosaic-painter chooses his stone material to work on in order to realize his artistic conception with the prepared stones (...) The building blocks obtained are joined together, the fugue corresponding to a logic immanent in the series, which manifests itself in the so-called continuum of the twelve tones. This principle immediately makes a composition familiar to the listener, it creates a harmonic bond that no longer has anything to do with functional tonality, but, without excluding these possibilities, results in a far stronger and more concentrated bound foundation."

But Heiß also got to know Arnold Schoenberg. He liked »E-F sharp-D« exceptionally well, and in 1932 he invited Heiß to speak about the composition in his master classes. Shortly thereafter, Schönberg was forced to emigrate.

While working as a music teacher in Spiekeroog (1928- 1933), Heiß founded an improvisation and jazz ensemble with which he went on tour.

"There were in our repertoire Brandenburg and other concertos by Bach. Handel, Corelli, Telemann and others, early medieval music and then modern music from Hindemith to twelve-tone music, and many works written for music educational reasons that I played with my students."

The diversity reflected in this repertoire is absolutely typical of Hermann Heiß and his artistic approach, which included everything and perceived many things simultaneously and with equal importance.

In 1933 Heiß moved to Berlin for eight years as a freelance artist, where he received recognition from the public and equally great rejection from the press. Thus it was written in a press review:

"On the occasion of a piano recital by the pianist Else C. Kraus, the listeners protested with whistles and heckling against the music presented, which was demonstratively applauded for it by a fanatical following. It was the music of the composers Paul Höffer. Norbert von Hannenheim, Hermann Heiß and Bela Bartok, i.e. of the Schoenberg circle, against which the healthily sensitive audience objected."

As was to be expected in view of the national socialist cultural censorship, the years that followed were marked by disappointment for Heiß. Although he composed a commissioned work for the 1936 Olympics, »Das Jahresrad» (»The Year's Wheel«), based on a text by his friend Edwin Redslob, for which Rudolf Laban designed a choreography, the performance of the work was harshly prevented.

In 1939 Heiß married the dancer Maria Muggenthaler, with whom he had two sons, Wendel and Nikolaus. After a short stay in 1941 at the Army Music School in Frankfurt, where he was discharged for refusing military orders, he went back to Darmstadt with his family and worked as a freelance composer, pianist, music teacher, and publishing associate. After Darmstadt was completely bombed out, the Heiß family moved to Jamnitz in southern Moravia, where he taught for six months in the music school evacuated from Vienna to there. After the dissolution of the music school, he and his family fled Czechoslovakia and returned to Darmstadt via Pilsen and the Bavarian Forest in 1946.

Now a completely new phase of life began for Heiß. He immediately began to compose again, organized events of New Music and in 1946 gave his lecture »Introduction to Twelve Tone Music« at the first Kranichstein »Ferienkursen für internationale Neue Musik« (»Summer Courses for International New Music«). In 1948 he was appointed teacher of composition and composition at the Städtische Akademie für Tonkunst in Darmstadt, and in the same year he chaired the working group »Ton und Klang im neuen Musikhören, Grundlagen einer Ton- und Klangbewegungslehre« (»Sound and Tone in New Music Listening, Foundations of a Theory of Tone and Sound Movement«) during the working conference »Neue Musik im Unterricht« (»New music in the classroom«) in Bayreuth. The summary of all theses and reflections on his new composition theory was published in 1949 under the title »Elemente der musikalischen Komposition (Tonbewegungslehre)« (»Elements of Musical Composition (Sound Movement Theory«).

He lived through the manifold upheavals of our century and and helped shape them.

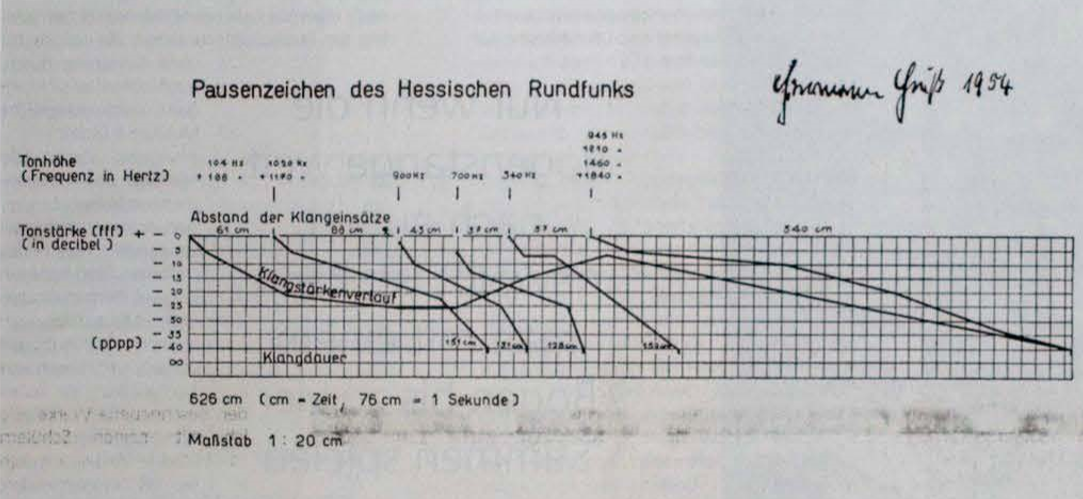

The Summer Courses of 1950 gave Hermann Heiß an important impetus: Werner Meyer-Eppler gave a lecture there on »Die Klangwelt der elektronischen Musik« (»The sound world of electronic music«) and thus provided the initial spark to deal with the completely new electronic sound generation and the resulting possibilities. In 1951 Pierre Schaeffer came to Darmstadt to talk about his »musique concrète«, and in 1953 Heiß realized his first »Elektronische Studie« (»Electronic Study«) in the studio of the WDR in Cologne. In the same year he was appointed head of a master class in composition at the Darmstadt Academy of Music. Now another area came back into the focus of his interest: improvisation. He formed improvisation groups that incorporated electronic means as well as traditional instruments. Heiß produced some utility music for radio, which was played until the 1980s, produced more electronic compositions in Cologne, and developed various devices with Eberhard Vollmer in Plochingen and later with the HEAG company to simplify electronic ways of working. In 1955 he was appointed head of the studio for electronic composition at the Kranichstein Music Institute. From then on, composers from all over the world came there to learn about the ever more advanced devices and electronic working methods.

In the following years, he created a large number of orchestral, chamber, stage, film and radio play scores, in which electronics were increasingly used in a style-defining manner. Outstanding from this creative period are perhaps the multimedia composition »LTM 61« (Light, Dance, Music) from 1961 with Alice Kaluza (dance) and Manfred Kage (light), the »Missa für Alt, Tenor, gemischten Chor und elektronisches Tonband« (»Missa for alto, tenor, mixed choir and electronic tape«) (1964), in which the problem of the notation of electronic music in interaction with voices was solved in a practicable way, and the »Variable Musik für vier Magnetophone« (»Variable music for four magnetophones«) (1967), which aimed at a spatial sound effect at an early stage.

Hermann Heiß performed his music throughout Europe and was a tireless protagonist of New Music in countless lectures. Yet his name is known to few today. As obsessed as he was with the music itself, as radical in his creative drive and will to express himself, as modest and unselfish he was as a person.

From today's point of view, there is not the one important contribution of Hermann Heiß to contemporary music, but a colorful palette of ever new ideas and projects, of diverse, sometimes diverging facets. As a dodecaphonic composer, an improviser, a pioneer of electronic music, also a tinkerer, a teacher, a theoretician and a tirelessly creative musician and human being, he lived through and helped shape the diverse developments and upheavals of our century.